Editor's Note: This article comes fromFirst class warehouse blockchain research institute (ID: first_vip1), reprinted by Odaily with authorization.

First class warehouse blockchain research institute (ID: first_vip1)

First class warehouse blockchain research institute (ID: first_vip1)

, reprinted by Odaily with authorization.

secondary title

What is inflation?

Inflation is an important psychological factor in consumption. It is precisely because of the fear that prices will rise tomorrow that many consumers choose to buy today. Therefore, a fall in prices ("deflation") should be avoided as it would depress consumption.

secondary title

inflation is a tax

Inflation is an anonymous tax. It is both extremely fair, because all economic agents are equally affected, but it is also extremely unfair, because it is the low-income earners who are most affected, and their purchasing power is reduced without a corresponding increase in income. But if inflation is indeed a tax, is the state the beneficiary? Yes, and no, explain why.

secondary title

Broadly speaking, inflation arises from two main factors:

The first is demand-pull economic growth. The principle is quite simple: the demand for a commodity gradually increases its price. During periods of strong economic growth, all prices rise. Wages will then rise, either because corporate profitability allows it, or because unemployment falls and the labor market tightens. This is the inflation everyone dreams of.

Another form of inflation is an increase in the money supply. Literally, if the currency reserves increase by 10% tomorrow, the prices of goods and services in the economy will also mechanically increase by 10%. This inflation is more insidious, and its effects are not always beneficial, and it can exist without economic growth. In this case, it is difficult for wages to match prices as businesses do not see a steady demand for their products.

Therefore, to understand inflation, focus on the money supply, the amount of money in circulation. So what are the pillars of money creation? is credit. Therefore, talking about inflation must talk about credit.

inflation and credit

Loose monetary policy, that is, a policy that promotes credit creation (such as keeping interest rates low) is inflationary in nature. It's one of the biggest tensions consumers face: abundant cheap credit doesn't go hand-in-hand with low inflation.

The link between inflation and credit is so strong that central banks make it their responsibility to maintain price stability.

The Fed and ECB often comment on this too: they agree that a healthy inflation rate should be around 2%. Therefore, the central bank must steer monetary policy in such a way as to avoid negative effects: authorize the creation of money (in the form of credit) to promote economic development, avoid inflation, and reduce purchasing power.

secondary title

If inflation is a tax, who pays the tax? The government benefits from modest inflation (notably that it dilutes debt, see below), but it's not a tax in the traditional sense (that is, large sums of money are levied by government authorities). In fact, inflation organizes the transfer of wealth among economic agents.

On one side are the holders of funds (notes, coins, checking accounts, etc.), that is, each individual. On the other side are large borrowers (regardless of their type of debt, public or private). Inflation is a transfer from holders of funds to borrowers. The first group of wealth (expressed in currency units) is depreciated every year by inflation. For the same reason, the second set of debts also loses value each year due to inflation. But this depreciation is a good thing: if I pay back 1,000 euros a month for 15 years, the purchasing power of that 1,000 euros will decrease over time. Today, the monthly repayment of 1,000 euros is still the same 1,000 euros, but after 15 years of inflation, its purchasing power is no longer what it used to be.

In essence, this is another curse for consumers: high inflation reduces purchasing power, but also greatly increases their debt sustainability, especially for the debt that dominates in volume and maturity (mortgage loans ) is concerned.

The same is true for households, countries or businesses: reasonable inflation can absorb debt more quickly. Therefore, the central bank is caught in a dilemma: either let inflation run its course and the government introduce fiscal policy to dilute debt, or actively fight inflation to protect purchasing power, but need to strictly control interest rates.

Inflation and Interest Rates

So is there an easy way to regulate the wealth transfer that inflation organizes in the economy? There must be, and that is through interest rates. Still the above example, suppose my total loan is 240,000 euros, the monthly repayment is 1,000 euros, and the annual interest rate is 5%. Now suppose my repayments are inflation-linked, meaning that the repayments are adjusted each year for the rate of inflation. For example, if inflation hits 2.5%, I pay back 7.5% per annum, which is 1500 euros per month instead of 1000 euros. This protects the lender, who can reduce purchasing power at any time as compensation.

A sound monetary policy also involves controlling the overall level of interest rates to regulate credit, money supply and ultimately inflation. During periods of high inflation, central banks raise interest rates, with the immediate effect of slowing credit and raising wages for lenders. But raising interest rates and restricting credit can also have a negative impact on the economy, making it harder for businesses (and individuals) to finance.

These observations explain why many loans are tied to variable rates. But instead of variable interest rates, government bonds use fixed interest rates. In other words, government (fixed rate) loans are far less inflation-proof than variable rate loans, especially in the long run. For example, real estate loans in France are mostly fixed rate, which effectively protects the borrower at the expense of the banks. In the US or UK, the mortgage is an "Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM)", meaning the loan has an adjustable interest rate and the financial institution is protected from inflation (at least to a certain extent).

secondary title

Bretton Woods

In Bretton Woods, tight controls on money creation meant that credit creation was also strictly limited. Severe restrictions on credit creation brought about a period of unprecedented stability.

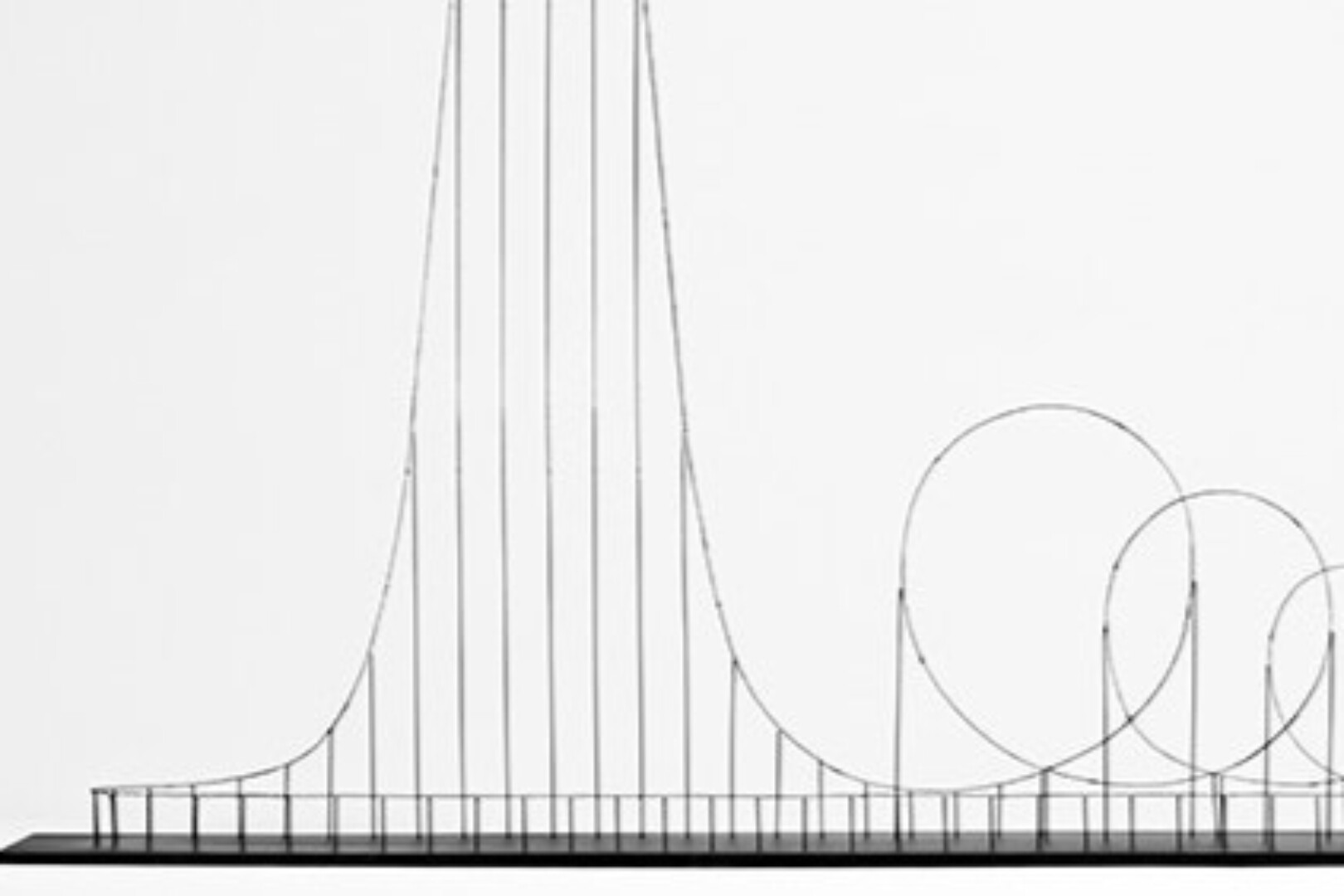

The graph below shows the percentage of the number of countries in a state of financial crisis between 1900 and 2008:

Image from the article Banking Crisis: The Equal Opportunity Threat

Inflation and digital assets

epilogue

Protocols for most digital assets have "hardcoded" inflation features. This is the case with Bitcoin, Ethereum, and many other cryptocurrencies. This kind of inflation is a monetary inflation, that is, it does not correspond to an increase in prices, but to the creation of money. Since no central bank regulates the quantity of money, no other inflation is possible, and therefore no credit creation is possible with these agreements. Therefore, if you want to borrow money, you have to see if someone is willing to lend your assets. Similarly, commercial banks are not suitable for this system, because their main function in real life is not to keep books, but to create credit.

The claim that digital assets are inflation-proof is absolutely true. But this comes at the cost of a lack of credit. In a digital currency-based economy, consumers may find that inflation is not tied to money creation (aside from what is "coded" in the protocol). They may discover that no bank charges account fees, but they may also realize that getting credit to buy a home is a miracle. In a world with a limited money supply, getting credit is tantamount to convincing someone to lend you their savings. All borrowers are competing with each other for limited resources. Also, no monetary inflation does not mean no inflation at all, just the disappearance of the second inflationary mechanism. If the digital currency can be used to buy oranges, then manufacturers are likely to raise the price of oranges in the face of strong demand.